News that the global Covid19 lockdown has led to two pandas in Hong Kong Zoo mating for the first time in ten years seems as good a reason as any for me to blog, for the first time, about sex. Or, more accurately, about sex and gender.

The ongoing and often toxic debate around sex and gender can feel intimidatingly complex and difficult to understand. So complex, indeed, that it is easy to conclude you need a PhD in human biology or Queer Theory, or both, to venture even just a mild opinion on the matter. And, when I say toxic, I mean toxic. Which is partly why I’ve not blogged about the issue before now. As Helen Lewis wrote in the New Statesman in 2018:

Most people have taken one look at the current debate over gender and decided to read [or write] about something less inflammatory, like the Israel-Palestine conflict.

But having read and thought about it (quite) a bit more, I’m not sure it is that complex, really. And I suspect the impression that it is complex serves the interests of the intellectually incurious people who think they can win a debate on the subject by shouting “clownfish”, “bimodal distribution”, or simply “there is no debate”.

Yet there is a debate to be had. Boris Johnson and his Cabinet of Fools are in power, and those undemocratically chanting “No Debate!” may come to find themselves on the wrong side of that argument. On the contrary, we desperately need to have a debate, as that is the only way we will identify and implement equitable and sustainable public policy solutions to the challenges faced by people who identify as trans. And those challenges are real.

At the same time, the sex-based oppression, violence and discrimination experienced by women is just as real (*understatement klaxon!*). Modern societies have made considerable progress in addressing this long-standing and acute inequality in the life experience of women and men, but there is still a very, very long way to go. So any debate about sex and gender – including how to address the challenges faced by trans people – needs to respect and be informed by this context. In particular, it needs to respect women’s hard-fought rights to single sex spaces. If the ever-growing number of trans identities are ‘valid’, then so are decades (if not centuries) of rape, domestic violence and murder statistics.

I’m not usually regarded as much of an optimist, but on this I do think it should be well within our capacity to navigate the potential tensions, and find equitable and sustainable policy solutions (which means they have to be accepted if not supported by a majority of the general population). If we can put a (cis) man on the moon, etc etc. I just think we need to be clear and honest about some basic facts of life.

Of course, it doesn’t actually matter what I think. I have no particular expertise on these matters (probably the main reason why I have not blogged about them before). And I have even less influence. I certainly don’t have anything ‘new’ to say that would add to what’s already been said by others. But as the barrister Allison Bailey noted recently, in the wake of trans activists slandering the world’s favourite author, JK Rowling, by publicly suggesting she is a sexual predator and child abuser:

For those of you on the sidelines, your silence will not protect you (but it will shame you). Speak up & stand with us.

So what follows is simply what I think are the basic, science-based facts that should be the starting point of the debate that we so clearly need to have. As I see it, we can agree on these facts, and then start to look for sustainable policy solutions to the evident conflict between the rights of women, and the rights of transwomen (men don’t appear to be too troubled one way or the other by the activities or rights of transmen). Or we can deny these facts, and continue to go nowhere fast (just ever more toxically).

Fact 1: Human biological sex is real, and matters. And, while biologically complex, it is binary: it is not a spectrum, and there are only two human sexes, not six (or ten). In the words of the blogger Andrew R (@excelpope): “obviously there is a huge amount of biological complexity here, which makes it easy to obfuscate the issue, but fundamentally, if you want a baby you need one person from each sex. You can talk about gametes, chromosomes and DNA until the cows come home, but if you start with two people from the same sex you will still never get a baby.”

OK, you’re not interested in making a baby, especially with me. (That’s fine, by the way – I’ve already fathered two more babies than I originally intended). But, were it not for biological sex, none of us would be here to have this debate.

So, sex is not “an ideological concept designed to exclude trans people from spaces”, and is generally observed and recorded, not assigned, at birth. If you disagree with this, then presumably you can explain how the sex of baby elephants is assigned when there are no elephant doctors to do the assigning. And, if you insist that we are very different to elephants – yet somehow similar to clownfish or that lone Komodo dragon in Chester Zoo – then try chimpanzees, with whom we share 98.8% of our DNA. There are no chimp doctors, either.

Not unrelated to the baby-making thing, sex is the basis for a great deal of oppression, violence and discrimination. Male humans (boys and men) tend to expect to be able to do and get whatever they want, even if that means disadvantage or even violence to female humans (girls and women). It’s the patriarchy, stupid. Or, as someone else has said, “empirically, penises have done bad”.

Yeah, I know, #NotAllPenises.

Fact 2: The existence of (very rare) Differences of Sex Development (DSDs) – some diagnosed at birth (about 0.02% of newborns are diagnosed with a DSD), but others only in later life – is entirely consistent with sex being binary. It is not evidence of sex being a spectrum. As the developmental biologist Dr Emma Hilton says,“DSDs are variations of anatomy, not variations of sex”. And no, intersex people are not as common as people with red hair, whatever Amnesty International says.

Fact 3: Along with other mammals, humans cannot change their sex. They can change the appearance of their sex, through surgery and/or the taking of hormones. However, most of those who identify as transwomen are, and evidently intend to stay, male-bodied. Indeed, not a few seem inordinately proud of their ‘girl dick’. But putting some glitter in your beard before you trawl the internet for PIV sex does not make you a lesbian. Not to beat about the bush (no pun intended), but only a man could genuinely think it does.

(That ‘genuinely’ is important, btw, as it is clear there is an awful lot of groupthink going on in this debate – TWAW, and Line 3 is definitely the same length as the line on the left, even though everyone can see it is shorter.)

Whatever, a modern, liberal society should accept and make appropriate legal provision for those who do change the appearance of their sex, as well as for those who simply believe that they have changed their sex by putting on lipstick, just as it should for those who are gay, lesbian, disabled, or female, and those who believe that there is an invisible, bearded guy living in the sky who created Earth in seven days. But the fact that some simpler species such as clownfish can change sex (in one direction only, as it happens), and that (female) Komodo dragons can produce offspring by parthenogenesis, adds absolutely nothing to this debate.

[Update, 18 November 2021: Since publishing this post in July 2020, I have resisted the temptation to add updates, as apart from anything else that would be a Sisyphean task. But, today, asked by BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour presenter Emma Barnett whether humans can change sex, Stonewall’s high priestess Nancy Kelly, said “no”. Which is pretty definitive.]

Fact 4: Despite the words often being used interchangeably, gender is not the same as sex. As to what gender is, there are any number of theories, but one is that it is a combination of (a) our own innate perception of being male or female (our ‘gender identity’), and (b) societal expectations of how we should look and behave, based on our sex (our ‘gender role’, or just ‘gender’). However, there is no scientific consensus that (a) even exists, outside the imagination of gender ideologists (who seem to me to be making it up as they go along). And (b) is simply a social construct, which therefore varies from region to region, and changes over time.

Or maybe gender is something else. As Andrew R (@excelpope) has suggested – possibly in jest – maybe gender was invented by bureaucrats in the 1960s to stop men answering “Yes please!” to the sex question on forms. But whatever gender is, it is not the same as sex, and sex is what matters. Women have been systematically discriminated against, raped and murdered by men for thousands of years because of their sex, not because of any ‘innate sense of their gender identity’ that they may or may not have. Put simply, if sex doesn’t matter, then nor do sexism and misogyny.

Of course, gender roles are problematic, as historically much if not all of the ‘social construct’ was constructed (mostly by men) to reinforce the sex-based roles of men and women (and of boys and girls), and so sustain the patriarchy. Modern societies have made much progress in breaking down the most harmful aspects of these gender stereotypes (and especially their coercive imposition), but they persist and indeed remain attractive, to a greater or lesser degree, to a great many people. And, generally speaking, that’s OK, even if it sometimes feels to me as if we’ve still not escaped the sad sexism and malevolent misogyny of the 1970s (when I had the misfortune to grow up).

Similarly, it’s OK, if you have a beard and a penis, to believe that you are woman, and that you are single-handedly broadening the bandwidth of ‘woman’ to include people with a beard and a penis who like to tinker with car engines. You just can’t expect anyone outside your narcissistic cult to share your belief, let alone expect the law to compel them to do so. In any case, maybe your energy would be better spent trying to broaden the definition of ‘man’ to include people with a beard and a penis who like to wear skirts, lipstick and a lot of bangles. That would seem to me to be a less scientifically-challenged endeavour.

Fact 5: Transwomen are not women, and transmen are not men. They cannot be, because humans cannot change sex (see Fact 3). They are transwomen, and transmen (even if they have had surgery and/or taken hormones to change the appearance of their sex). And there’s absolutely nothing ‘wrong’ with being a transwoman or transman.

Which means a modern, liberal society should accept and make appropriate legal and other provision for the specific needs of transwomen and transmen, to ensure they can live their lives free from discrimination and abuse. As already noted, we accept and make appropriate legal and other provision for people who believe that some invisible guy who lives in the sky created the Earth in seven days, and will stop us getting cancer as long as we go to church and sing a few songs every Sunday. So, we can do the same for men who believe that they are a woman, and vice versa.

To take a mundane but important example, in workplaces and other public spaces, transwomen and transmen should not have to use communal, single sex toilet, shower or changing facilities in which they might feel uncomfortable or unsafe. But that does not mean all such communal single sex facilities should be redesignated as gender-neutral. It simply means there should always be adequate provision of gender-neutral (or single user) facilities, in addition to single sex communal facilities for women and men.

Many businesses and organisations have ticked the ‘Stonewall Law’ box simply by spending £15 on changing the signs on the doors of their single sex facilities. But – doh! – women and girls can’t use urinals. And why should women and girls have to use communal, gender-neutral facilities in which they might feel uncomfortable or unsafe? Why should the feelings of a numerically tiny group of mostly male-bodied and male-socialised people trump those of 51% of the population? As lawyer Naomi Cunningham says on the Legal Feminist blog:

What some male commentators on this subject fail to grasp is what a rigorous training in fear women receive from an early age. We are taught that men are a source of danger. We are told it is our responsibility to keep ourselves safe from the ever-present risk of male violence. We learn to limit our freedoms. We try not to be out alone late at night. We learn to be alert to the possibility of being followed; not to make eye contact; to shut down drunken attempts to chat us up without provoking male rage; to walk in the middle of the road so that it’s harder to ambush us from the shadows; to conduct a lightning risk assessment of every other passenger on the night bus; to clutch our keys in one hand in case we need a weapon; to carry a pepper spray, or a personal alarm.

We are systematically trained in fear.

And then we are told that we must lay aside the fears we have obediently learned at a moment’s notice if a person with a male body asserts a female identity. Well, fear doesn’t work like that.

Sure, it will cost businesses and organisations more than £15 to ensure adequate provision of gender-neutral or single user facilities, alongside communal single sex facilities, to provide for the needs of the less than 1% of the population that identifies as trans. But doing the right thing is rarely the cheapest option.

Similarly, male-bodied transwomen should not be incarcerated alongside female prisoners, and transwomen should not be playing in women’s sport: it’s potentially dangerous to their female opponents, in contact sports such as rugby, but more importantly it’s unfair to the women left out of the teams/crews or denied a place on the medal rostrum.

There’s a simple reason why you hear about transwomen playing in women’s rugby teams, for example, but never about transmen playing in men’s rugby teams. It’s the very reason we have ‘women’s sport’. As sports scientist Ross Tucker explains, if we didn’t, “the champion in every single event would be male. In fact, the top 3,000 (at least) would be. That’s not how it’s meant to be.”

Oh, and men do not get pregnant – if they did, the world would look very different, and we almost certainly wouldn’t be having this debate. Some transmen get pregnant, but only if (and because) they have retained the necessary (i.e. female) reproductive organs.

Finally, if you believe that TWAW because ‘some people are born in the wrong body’, you should maybe read this 20-year-old article. A long and disturbing read, it describes the phenomenon of people who hack off their own (perfectly healthy) limbs – or persuade a surgeon to do so somewhat less violently – because “I have always felt I should be an amputee” or “I have a desire to be myself, as I ‘know’ or ‘feel’ myself to be.” This once extremely rare ‘identity disorder’, apotemnophilia, has become vastly more common since – you guessed it – the invention of the internet, where hundreds of apotemnophiles have now formed online communities, in which they share images of amputees (including amputee porn), affirm each other’s beliefs and desires, and discuss how best to procure a surgical amputation. Some apotemnophiles trace the onset of their absolute belief that they should have fewer than the four limbs they were born with back to when they were a young child. Sound familiar?

Fact 6: Er … there is no Fact 6. To my mind, five simple, science-based facts are all you need to start working on solutions. It’s not actually necessary to delve into “the cis privilege of white, middle-class feminists” (to quote one white, middle-class and ostensibly feminist former colleague of mine with whom I strongly disagreed on this issue), acquire a detailed knowledge of 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency, or speculate about the prevalence of autogynephilia and ‘Pornhub culture’ among transwomen. Except that, as journalist Jo Bartosch was one of the first to point out, the latter might actually be highly relevant – even central – to what’s going on:

In this era of apparent sexual freedom, the suggestion that sexual arousal might be the reason behind the rising numbers of people ‘coming out’ as transgender is still strictly verboten. Perhaps I’m a cynic, but to my mind kink is a more convincing explanation than the trapped female ‘souls’ that Layla Moran MP claims to be able to see.

But acknowledging the possible sexual driver for many of those who transition is directly at odds with the mainstream media narrative. Transgender women are almost always portrayed as victims, with late-transitioning white computer programmers in the Home Counties weaponising the deaths of Brazilian transsexuals to bolster their standing in the oppression stakes. This insistence of vulnerability plays into a sexist stereotype of femininity, and in my opinion is part of the fetish.

A case in point: self-styled ‘defender of extreme pornography’ and transgender activist Jane Fae has claimed that trans women are at risk from the likes of the allegedly ‘transphobic’ veteran broadcaster Jenni Murray. This is ludicrous. It is, after all, men who most often kill trans women.

Whatever, there’s certainly no need to start calling women ‘womxn’ or ‘menstruators’. As the Australian academic Petra Bueskens wrote in the wake of the furore over JK Rowling daring to suggest that transwomen are not women and that ‘woman’ is “not a pink brain, a liking for Jimmy Choos or any of the other sexist ideas now somehow touted as progressive”:

When Daniel Radcliffe repeats the nonsensical chant transwomen are women, he’s not developing an argument, he’s reciting a mantra. Transwomen are women is not an engaged reply. It is a mere arrangement of words, which presupposes a faith that cannot be questioned. To question it, we are told, causes harm—an assertion that transforms discussion into a thought crime. If questioning this orthodoxy is tantamount to abuse, then feminists and other dissenters have been gaslit out of the discussion before they can even enter it.

This is especially pernicious because feminists in the West have been fighting patriarchy for several hundred years, and we do not intend our cause to be derailed at the eleventh hour by an infinitesimal number of natal males, who have decided that they are women. Now, we are told, transwomen are women, but natal females are menstruators. I can’t imagine what the suffragists would have made of this patently absurd turn of events.

If we are prepared to spend (quite a bit) more than £15.00, we can change society’s infrastructure (and laws) to meet the needs of the relatively small number of trans people, just as we have made some progress in doing so for, say, the much larger number of disabled people. When I was a kid, accessible facilities for people with a disability were practically unheard of, as were (gender-neutral) baby-changing facilities. Now, they are commonplace.

And before you shout “But disabled people are still discriminated against!”, I know they are (not least because my son is disabled). As are black and ethnic minority people, and women. So maybe Fact 6 is that, whatever changes we make to society’s infrastructure and laws, trans people will, sadly, continue to face a degree of discrimination and unfair treatment. Maybe eventually we’ll get to nirvana, but we’re not there yet.

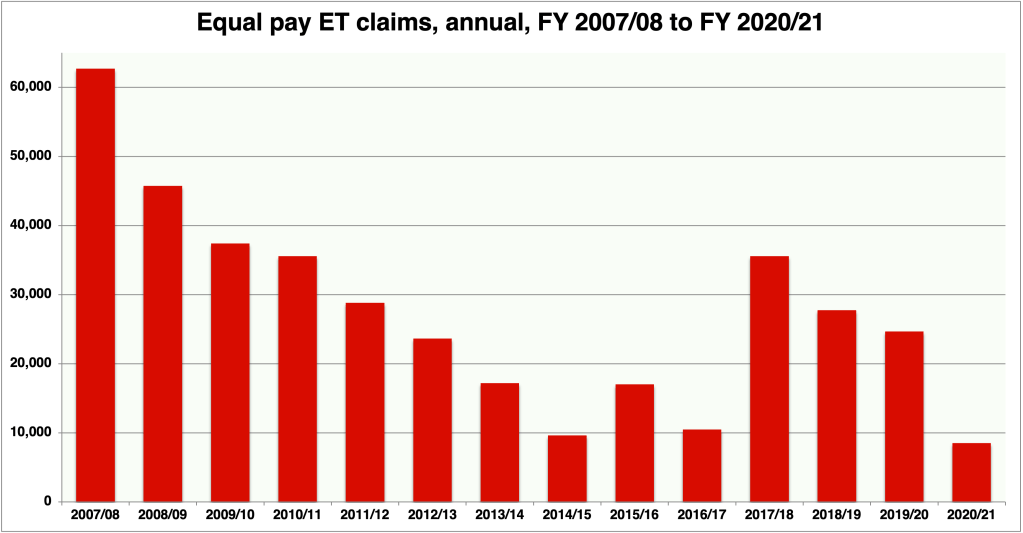

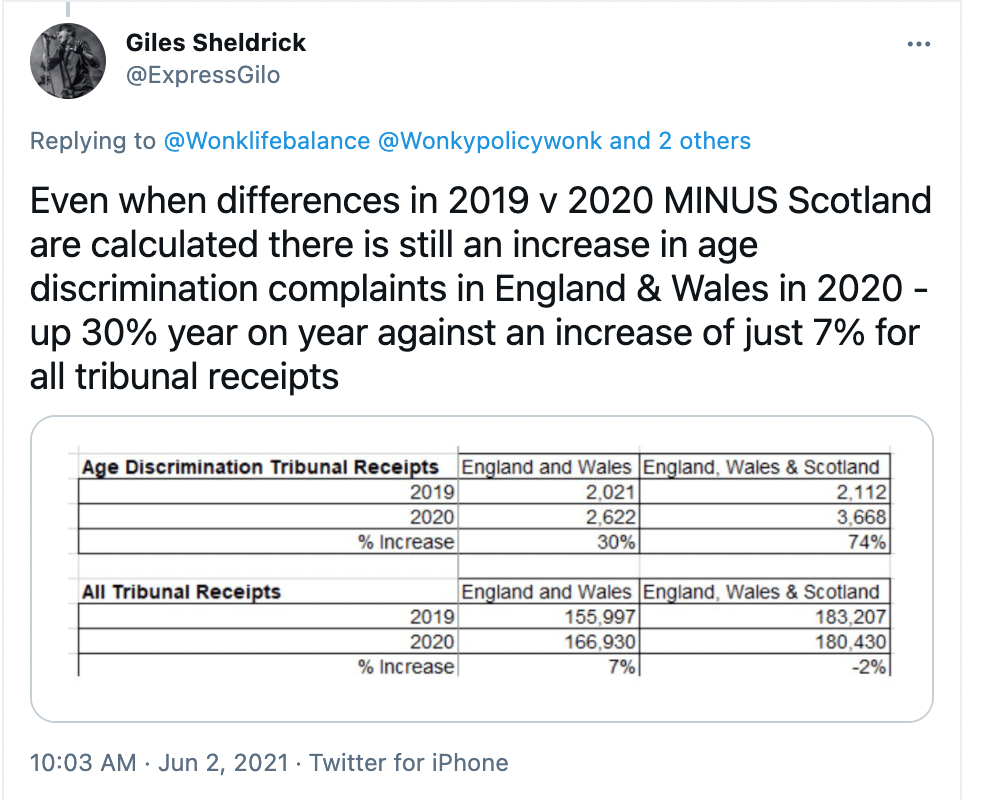

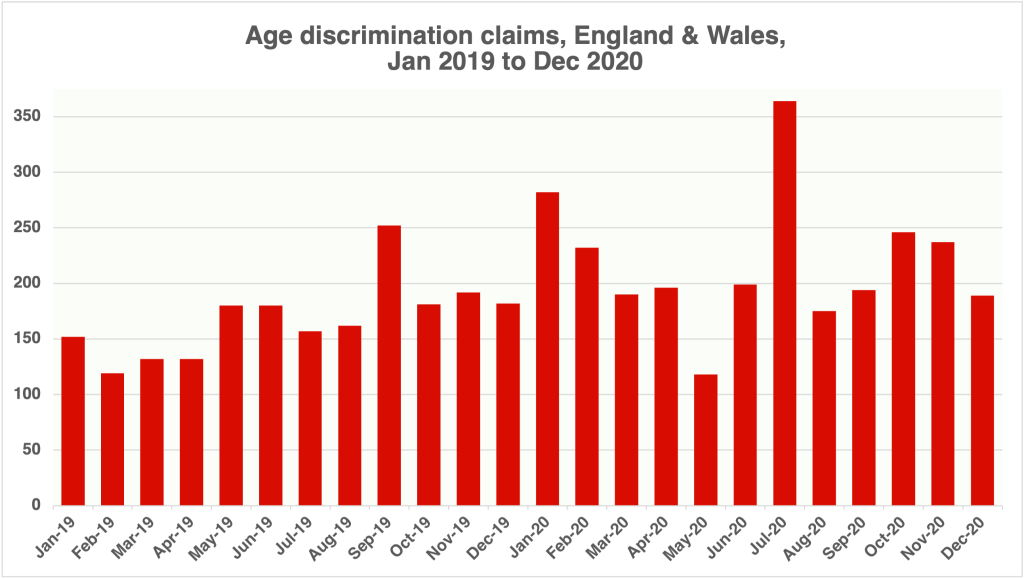

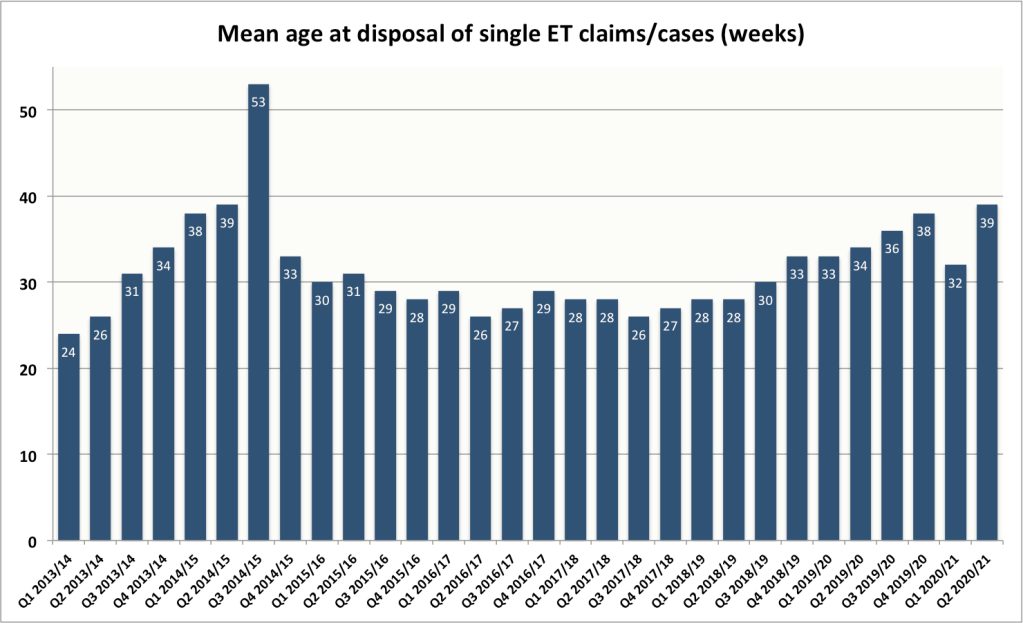

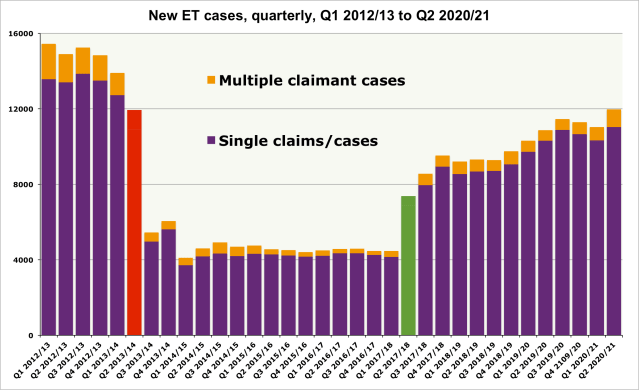

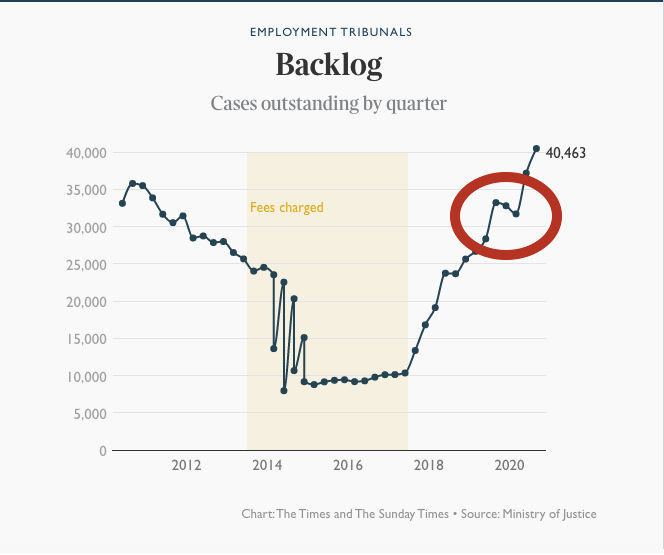

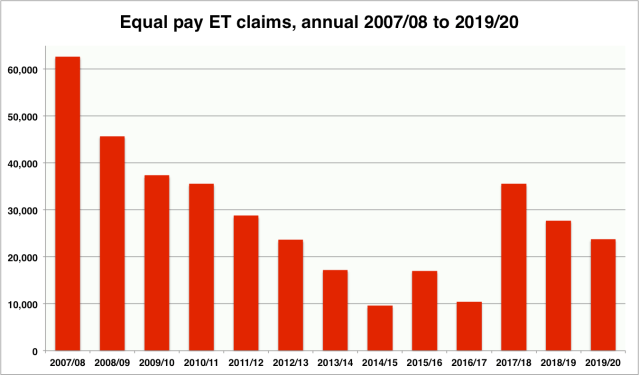

This means that some trans people will have to assert their rights by, for example, bringing employment tribunal claims, just as all too many disabled and BAME people have to assert their rights at work by bringing employment tribunal claims for disability and race discrimination, and very large numbers of women have to assert theirs by bringing claims for sex or pregnancy/maternity discrimination, or unequal pay. Unfortunately, there is no magic, pink and powder blue-striped policy wand that government ministers can wave to make life trouble-free for everyone. For many people, life will sometimes involve serious struggles.

In my experience, women tend to understand this unfortunate ‘fact of life’, even if many activist transwomen (and their equally vocal male ‘allies’) appear not to. I refer you to Facts 1 and 3, above.