This post – about my son’s recent reassessment for Personal Independence Payment (PIP) by the DWP – will only be of interest to those applying for PIP or advising those doing so, and is posted in case it is helpful in any way. It is also a case study in how poor the DWP’s decision-making is, and possibly offers a couple of lessons to claimants and advisers.

Sam’s disabilities result from him having suffered severe pneumococcal meningitis in December 1999, when aged 20 weeks. The meningitis left him profoundly deaf, hemiplegic, epileptic (since resolved), and with mild learning difficulties (not apparent and diagnosed until some years later). In June 2001, Sam received a cochlear implant at Great Ormond Street Hospital, and in 2007 he received a bilateral cochlear implant.

In March 2016, having been in receipt of Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for more than a decade, Sam was reassessed and transferred over to Personal Independence Payment (PIP), at the standard rate for both Daily Living (a total of 8 points for ‘communicating verbally’, ‘reading’, and ‘budgeting’) and Mobility (10 points for ‘planning & following a journey’). And, as Sam was assessed by the DWP as not being able to manage his own financial affairs, including his PIP claim, I was made his ‘Appointee’.

Looking back now, I could perhaps have queried some of the DWP’s allocation of ‘descriptors and scores’ in 2016, such as just 2 points (out of a possible 12 points) for ‘communicating verbally’, which to my mind seemed a bit harsh for someone who is profoundly deaf.

However, overall, the PIP award did not seem unreasonable, given that Sam was still a child, and in financial terms it was not dissimilar to what Sam had been receiving previously under DLA. Furthermore, the award letter only gave the ‘descriptors’ that had been allocated to Sam, so I had no way of knowing whether he actually fitted better in different descriptors (I was not aware that the full set of descriptors is in fact available online). And, as a family, we had other priorities, such as challenging our local education authority in relation to their funding of Sam’s place at his residential school for the deaf.

Fast forward to June 2018, when the DWP called Sam for reassessment. However, as the DWP was only able to offer a ‘consultation’ on a week-day, at an assessment centre in London, and as Sam was away at his residential school (near Newbury) most weeks, the assessment did not take place until 4 March 2019, when Sam was home for half-term. I accompanied Sam to the ‘consultation’ as his Appointee.

The ‘consultation’ was a joke. At the outset, the assessor apologised for English not being her first language, and explained that she had only moved to the UK (from the Philippines) two months previously. Perhaps this shouldn’t have mattered, but it did mean, for example, that we later wasted 15 minutes after the assessor leapt on the fact that Sam has a provisional driving licence, which she immediately assumed must mean Sam has passed a driving test and drives a car. In fact, Sam has never sat behind the wheel of a car, and (like many of his deaf peers) only has the licence as a handy means of ID. But the assessor had never heard of and did not understand the concept of a provisional driving licence, so – while I was only supposed to be observing – I had to intervene repeatedly to explain it to her, as Sam himself was (understandably) unable to do so.

Whatever, on 12 March, the DWP terminated Sam’s PIP award, having allocated him just 2 points for Daily Living (for ‘communicating verbally’), and zero points for Mobility. So I lodged a request for Mandatory Reconsideration, which in July resulted in the DWP adding just 2 points for Daily Living (making budgeting decisions).

Sam’s disabilities are permanent, and will never improve. He will always be profoundly deaf, so will always rely on his cochlear implants for (less than perfect) communication, and he will always have the learning difficulties that prevent him being able to make even the most simple budgeting decision. So, surprised and disappointed by this ‘nil award’ by the DWP, and its confirmation on Mandatory Reconsideration, I lodged an appeal to the Tribunal.

However, on 22 August, I was equally surprised to receive a one-page letter from the DWP offering to grant PIP at the standard rate for Daily Living (i.e. at least 8 points), and the enhanced rate for Mobility (i.e. at least 12 points), on condition I withdrew my appeal to the Tribunal. This ‘Lapse Appeal Offer Letter’ did not include any reasoning for this somewhat dramatic change of position (see image below), and when I telephoned the DWP caseworker (as requested), he was unable to offer any explanation for the (somewhat unexpected) Mobility element of the award, other than that it is “for health and safety reasons”. Given that, only a few weeks previously, the DWP had twice allocated Sam zero points for this activity, and that in 2016 (i.e. when not yet an adult) he had only been allocated 10 points for this activity, I concluded that this 12-point element of the offer was unsustainable, and that it was an attempt to induce me into withdrawing my appeal, only to have the award reviewed (and lowered) at some point in the future.

Furthermore, the DWP’s letter did not set out which descriptors (and points) had now been allocated to Sam for each Daily Living activity, and the caseworker was unable to answer my questions on this, as he said he no longer had the file. So, for all I knew, Sam might only have been allocated 8 points for Daily Living, the lower threshold for the standard rate, in which case that allocation might also be at risk from a future review. Accordingly, I decided to decline the ‘offer’ and continue with my appeal, in the hope that the Tribunal would clarify these matters and confirm the correct allocation of points for Daily Living and Mobility.

I was then further surprised, on 16 September, to receive a telephone call from a clearly more senior caseworker, who first bewildered me with a rapid-fire monologue about the various descriptors – most of which I had never seen or heard of before, of course – and then offered to grant Sam enhanced rate for both Daily Living and Mobility, if I withdrew the appeal. Still suspicious, and not having any of the past documents to hand (as the telephone call had come out of the blue), I asked the caseworker to set out the details of the offer – including the points allocated for each activity – in writing, so that I could consider the offer properly, together with the past documents.

At that point, the caseworker adopted a bullying tone, stating: “You have to make a decision now, as I have to tell the Tribunal what is happening”. Noting (with respect) that this was her problem, not mine, I repeated my request for written details of this latest assessment of Sam’s disabilities. The caseworker then said she would put the offer in writing.

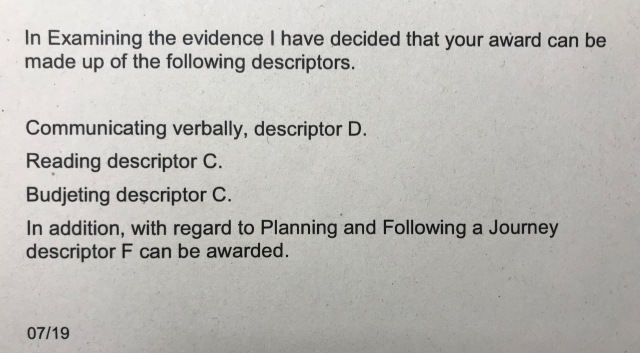

A few days later, I received a one-page letter from the DWP, but this did not set out the details I had requested. It simply gave the letter of the descriptor now allocated to four activities (three under Daily Living, and one under Mobility), without stating the full text of those descriptors (see image, below). So, when the DWP caseworker telephoned me again, chasing a decision, I rejected her offer and decided to continue with the appeal to the Tribunal, despite her offer being the highest possible award (in monetary terms).

Yep, that’s the DWP’s explanation of its new decision, in its entirety.

Just two weeks later, however, I received the 145-page appeal ‘bundle’ from the DWP, with all the documentation relating to Sam’s PIP claim since 2016, including a detailed reasoning – spread over a full five pages – of the latest allocation of points in relation to the four activities above, totaling 14 points for Daily Living, and 12 points for Mobility (planning & following a journey). And this five-page explanation of the award was dated just the day after I had last spoken to the (more senior) DWP caseworker. Had she provided me with this written explanation at that time, I would have been happy to accept the offer and withdraw the appeal. So, I wrote to the Tribunal, setting this out.

However, it is not possible to withdraw an appeal once the bundle has been issued, it seems, so at the end of October I found myself nervously taking a seat before a judge and two lay panel members at a hearing centre in central London. I had prepared a short speech, explaining why I had insisted on coming this far despite the DWP having offered the highest award possible (in financial terms), but it was not needed. With the two lay members smiling and nodding in agreement, the (kindly) judge quickly explained that, having read all the papers, they had already decided to allow the appeal and confirm the DWP’s award of PIP at the enhanced rate for both Daily Living and Mobility. Barely 20 minutes after arriving at the hearing centre, I was back on the street, clutching a letter from the Tribunal confirming their ruling.

So, a happy ending, with Sam on a higher rate of PIP than I most likely would have settled for in March 2019, had it been offered at that point. And Sam now has a Tribunal-confirmed benchmark of descriptors and points to take into the next reassessment in five years’ time: 8 points for communicating verbally; 2 points for reading & understanding signs, symbols & words; 4 points for making budgeting decisions; and 12 points for planning & following a journey.

But this is no way to run a disability benefits system. I wonder how many claimants, and especially those lacking basic computer skills or confidence – both the Mandatory Reconsideration request and appeal to the Tribunal have to be completed online – drop out when faced with the kind of nil award given to Sam by the DWP in March, and confirmed at Mandatory Reconsideration in July. And what if I had accepted the DWP’s first telephone offer, in August? Sam would have lost out on more than £7,500 (the difference between standard and enhanced rate for Daily Living) over the next five years.

My advice to any PIP claimant, therefore, is twofold: firstly, get your hands on the full set of descriptors at the outset, so that you can arm yourself with your own assessment of which descriptors should be allocated to you; and secondly, be prepared to stand your ground, even if that means going all the way to the Tribunal. According to the latest official statistics, 75% of all PIP appeals are allowed by the Tribunal at a hearing, despite the apparent practice on the part of the DWP of making highly tempting ‘offers’ to those with strong appeals, in return for withdrawal of the appeal.

And that latter practice may well explain why, according to the DWP, “the proportion of [PIP] appeals lodged which lapsed [i.e. where DWP changed the decision after an appeal was lodged but before it was heard at Tribunal] has gradually increased since 2015/16 – from 4% in that year, to 17% in the latest two quarters (October 2018 to March 2019)”. In short, the Tribunal is allowing 75% of appeals, despite the DWP conceding almost one in five appeals before they get to a Tribunal hearing/ruling. Which means the real success rate on appeal is 79.2% (17 + (83 x 0.75)). Well played, DWP.

In 2017-18, according to the justice minister’s response in June 2019 to a Parliamentary Question by the Labour MP Rushanara Ali, the DWP funded 29% of the £1 million cost to HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) of social security appeals (including PIP appeals). That contribution may well have gone up since, but if I was a senior official at HMCTS, or a minister in the Ministry of Justice, I’d be demanding a lot more.