Earlier this week on this blog, I noted the traditional attempts by policy wonks to exploit the commercial confection that is Father’s Day to call for reform of statutory paternity leave, including a new joint report by the think tank Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP) and the campaign group Pregnant Then Screwed (PTS). And, now that I’ve stopped tearing my hair out, I’m ready to set out a few thoughts on that report.

The report’s key policy recommendation is: “increase the length of non-transferable paternity leave to a minimum of six weeks and pay it at 90% of income in line with current statutory maternity pay”. Because the CPP’s analysis of OECD data from 1975 to 2021 finds that “a paid entitlement of at least six weeks [in OECD countries] is associated with a decreased incidence of both gender wage gaps and labour force participation gaps, by 4.0 and 3.7 percentage points respectively”. The CPP and PTS then conclude from this that “increasing the length of paternity leave [from two to six weeks] has the potential [sic] to reduce inequalities in pay, career progression, employment, and the provision of childcare”. And, apparently, this would only cost up to £1.6 billion a year – that is, a mere 43% increase in the current total spend on statutory maternity, paternity and other parental pay of some £3.7 billion per year, and a 32-fold increase in the current annual spend on statutory paternity pay of just £50 million a year.*

Memo to self: breathe, Wonky, breathe.

Yes, increasing paid paternity leave from two to six weeks, and paying it at 90% of earnings instead of the current, ludicrously low flat rate of £172 per week, might reduce the UK’s gender pay and labour force participation gaps. Or it might not – correlation does not imply causation, and there might well be other reasons why those OECD countries with better paternity leave provision than the UK also have smaller gender pay and labour force participation gaps.

Indeed, the CPP/PTS report concedes that “parental leave policies are far from the only barrier to mothers’ participation in the labour market – with the accessibility of childcare, gender norms and workplace culture also being highly influential”, and that “the countries that offer longer periods of paid paternity leave could be significantly different from those that don’t, and these differences may be correlated with [the lower] gender gaps in the labour market.”**

So it is possible – or even probable, given what we know about the UK’s totally shit childcare system, gender norms and workplace culture – that increasing paid paternity leave from two to six weeks and paying it at 90% of previous earnings would have very little if any impact on the UK’s gender pay and labour force participation gaps.

In short, the CPP and PTS want the Government to gamble up to £1.6 billion a year on the reliability of the CPP’s heterogeneous difference-in-differences regression model.

On the other hand, we can say with near certainty that increasing paid paternity leave from two to six weeks and paying it at 90% of previous earnings would not deliver the policy goal of more equal parenting – which, as the report notes, is “critical to women’s empowerment and increased earnings”. Because six weeks of paid paternity leave is still only six weeks. And only four weeks more than we have now.

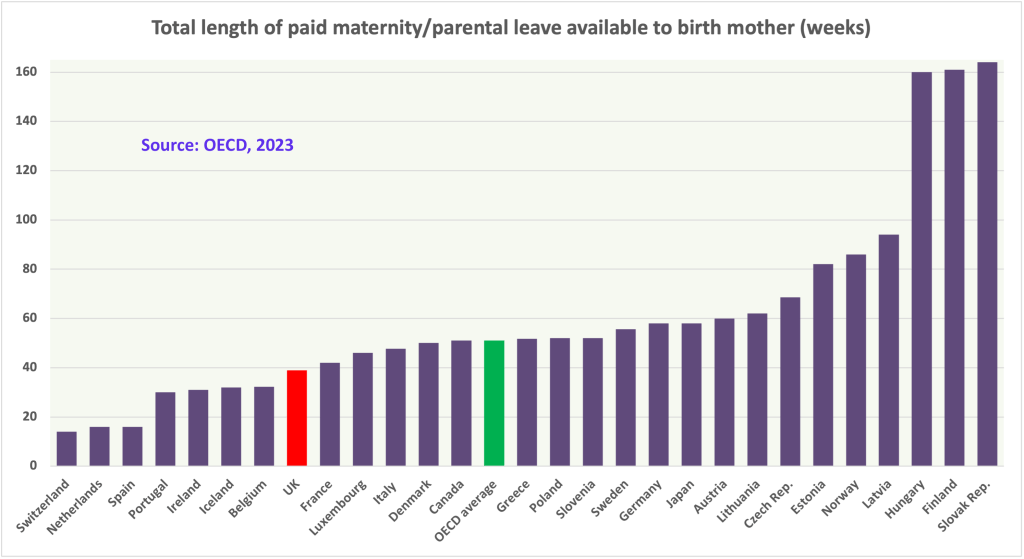

We have known for years, from the government’s own research, that – for very good reasons, including the need to recover physically and mentally from nine months of pregnancy and giving birth – the average new mother takes 39 weeks of maternity leave (that is, her full entitlement to paid maternity leave). And that’s very unlikely to change just because the child’s father can be at home with the mother for up to six weeks immediately after the birth, instead of just one or two weeks. Because that 39 weeks is not excessively long. In fact, as the following chart shows, 39 weeks of paid leave is short by international standards.

So, even if the average new father were to take the full six weeks of paid paternity leave proposed by the CPP and PTS, he would still only be taking 13% of all the paid parental leave taken by his family, with the birth mother taking 87%. And, as paternity leave is tied to the time immediately after the child’s birth, he’d be taking all of his leave when the child’s mother is also at home. So, unlike the child’s mother, he wouldn’t be doing any solo caring or parenting. As the Fatherhood Institute noted in 2019, in their response to the Government’s still not concluded consultation on reform of parental leave, “leave taken by the father/ partner at this point does not offer the family flexibility or choice, or incentivise particular parental behaviours”.

Perhaps the CPP and PTS think that the Fatherhood Institute is wrong on this point, and hope that more fathers taking more paternity leave immediately after the birth would lead to greater take up by fathers of parental leave later in the child’s first year, under the chronically failing Shared Parental Leave (SPL) regime introduced in 2015. As the report acknowledges, analysis by Maternity Action indicates that a mere 2% of new mothers who start on statutory paid maternity leave use the SPL scheme to transfer some of that paid leave to the child’s father. But if that is their hope, they don’t say so in the report. And, given the (well known and understood) reasons for the failure of the SPL scheme, it would in my view be wildly optimistic to think that increasing paid paternity leave would lead to significantly greater use of the SPL scheme.

Whatever, the CPP and PTS policy recommendations would leave the chronically failing SPL scheme in place, and unreformed. Which to my mind is yet another lost opportunity to make the case for scrapping the SPL scheme and creating a more equitable and ‘father inclusive’ system of parental leave that properly reflects the different purposes of maternity, paternity and parenting leave. As I’ve said elsewhere, any such system should deliver an individual (non-transferable) right to a significant period of parenting leave for fathers (and other second parents), while protecting and ideally enhancing the existing statutory rights of birth mothers.

None of which is to say that our paid paternity leave provision should not be more generous than it is now. Given the ‘health and safety’ purpose of paternity leave – to support the mother at and immediately after the birth – there is a very strong case for it to be paid at 90% of earnings, just like the first six weeks of maternity leave, rather than at the ludicrously low basic rate. Furthermore, eligibility needs to be widened – at the very least, it should be a Day One right (as the Labour Party already proposes). And, under the 6+6+6 model of maternity, paternity and parenting leave proposed by Maternity Action, fathers would be able to use some (or even all) of their entitlement to six months of paid parenting leave to extend their two weeks of paternity leave, should they want to do so.

Furthermore, it goes without saying that all parental leave should be (much) better paid. In March, an important new report by the Fabians Society, In Time of Need, highlighted that the UK’s average income replacement rate for maternity leave is the third lowest in the OECD: “Almost every other European country pays an earnings-related maternity (or parental) payment for most or all of the duration of statutory leave [and] replacement rates are high, almost always falling between 75% and 100% of earnings”. But in the UK the earnings replacement rate is just 29.5%. The Fabian Society propose that all statutory maternity, paternity and parenting pay be paid at 50% of previous earnings, subject to a cap.

So, frankly, it is deeply disappointing to see the CPP and PTS call on the Government to spend up to £1.6 billion a year on a minor legal reform that would most likely not deliver the claimed economic benefits, and would certainly not deliver the overall policy goal of more equal parenting. We’ve wasted an entire decade on the chronic policy failure of Shared Parental Leave, and now think tanks and campaign groups are wasting more time and energy on performative dad dancing.

* I can’t find an explanation of the “up to £1.6 billion” costing cited in the Guardian article anywhere, but my own (quick and dirty) number crunching indicates the total extra cost would be up to £1.4 billion. This assumes (a) male median weekly pay of £683 (ONS, April 2022) and (b) 100% take-up of the full six-week entitlement among 400,000 new fathers, and it allows for the current (near negligible) spend on statutory paternity pay. Clearly, in practice, take-up would not be 100%. But then the claimed economic benefits would of course be diminished too.

** If you want to read about “time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity”, there is a technical appendix to the report that seeks to explain how they have cleverly wonked away the possibility that they are just presenting correlation as causation. But £1.6 billion is one helluva gamble to take on a think tank’s heterogeneous difference-in-differences regression model.

[Update: Business minister Kevin Hollinrake’s answer to a recent parliamentary question suggests he has not been wowed by the CPP/PTS report. And, in related news, on 29 June the Department for Business & Trade finally published both its response to the above-mentioned Good Work Plan: Proposals to support families consultation, and the evaluation of the Shared Parental Leave scheme that it started in early 2018. Needless to say, the SPL evaluation report is not worth the 163-pages of paper it is printed on, and the similarly underwhelming consultation response proposes just one reform to paternity leave: subject to legislative change, this will no longer be tied to the time of birth, and will be available to take at any point throughout the child’s first year. Which may or may not be a good thing.]

Pingback: More bad dad dancing? | Labour Pains